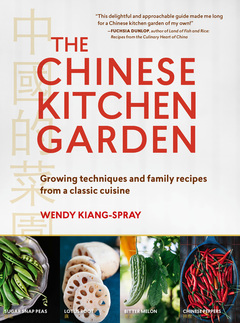

The Chinese Kitchen Garden, released by Timber Press in February 2017 is a beautiful introduction to growing and cooking a classic cuisine. Read an excerpt below to learn why this book was written for gardeners of all experience levels, home cooks, and those who enjoy reading about food and culture. The Chinese Kitchen Garden is also an excellent guidebook for shoppers to carry through the Asian grocer's produce aisle. Finally, a guide that demystifies the unique, nutritious, and delicious vegetables you've always wanted to know more about!

Available now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powell's, Indie Bound, Politics & Prose or your favorite book seller.

Available now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powell's, Indie Bound, Politics & Prose or your favorite book seller.

The Chinese Kitchen GardenWendy Kiang-Spray’s family has a strong culinary and gardening tradition. In The Chinese Kitchen Garden, she beautifully blends the story of her family’s cultural heritage with growing information for 38 Chinese vegetables—like lotus root, garlic, chives, and eggplant—and 25 traditional recipes, like congee, dumplings, and bok choy stir-fry. Organized by season, you’ll learn what to grow in spring and what to cook in winter. Throughout, you’ll learn how to improve soil, make compost, sow seeds, and more.

Order now from your favorite bookseller to receive the book before the next gardening season!

|

Excerpts from The Chinese Kitchen Garden

In the Garden |

...Those who love bitter melon might speak of the bitter tang or the refreshingly cooling quality of the bitterness. The taste is hard to describe so you must try it for yourself at least once. If it helps, know that bitter melon is believed to lower blood glucose and lipid levels and has been found to have antiviral and antioxidant properties. In fact, especially regarding its benefit to diabetics, the bitter melon has been dubbed the “magic melon.”

‘Hong Kong Green’ is similar to the variety my family grows. These 8- to 10-inch fruits are a bright green color and have relatively smooth bumps. It is widely grown in Canton and Southeast Asia and is the bitter melon used in the Cantonese cuisine that I grew up eating. Today, in Asian supermarkets and seed catalogs, a white variety called 'White Pearl' is available. While my parents prefer the taste of the green Cantonese bitter melon, the pure white variety, popular in Taiwan, is quite a beauty and would be a great one to try as well. Growing Chinese bitter melon requires some attention at the outset because the plant has a longer germination period, sometimes up to 30 days. Soaking the seed for a couple of hours in lukewarm water or nicking the thick seed coat prior to sowing your seeds may help speed the germination process. It is possible to directly seed in the garden, but the soil must be warm (about 70 degrees Fahrenheit) or the seed may rot before a cotyledon ever sees the light of day. For gardeners without an exceptionally long growing season, it may make the most sense to start bitter melon from seed indoors several weeks before the last frost date. A soil thermometer can help determine when it is a good time to sow seeds or transplant seedlings. Once established, the bitter melon vine will love a sunny spot in the garden with an 8-foot-tall structure to climb up and over. Despite being a climber, the vine will never grow out of control. Begin harvesting approximately 60 days after planting out—a slight smoothing out of the bumpy ridges on the melons will let you know they’re ripe. Pick the fruits while they’re still green and about 6–12 inches long. To save seed, allow a couple of robust gourds to yellow on the vine. Then, either use your favorite seed saving method or allow nature to take over in its unique way with bitter melon. At a later stage of maturity, the melons will split open on their own, displaying individual seeds covered in bright red, goopy mucilage. At this point, you can collect the seeds and rinse them off, or you can leave them on the plant or even allow them to drop to the ground. Ants and other insects will carry the mucilage off and you’ll be able to collect your seeds the next day. The red goop is sweet and edible. ******************************************************************************** ...One day, I asked my father about radishes he used to grow and he went into a reverie about the rows and rows of radishes in his garden in China. After harvesting, he would store them by cutting off the green tops and burying the radishes in pits outside, under dirt and then later, snow. He talked about the hot flavor that becomes frost-sweetened in early winter. Once you crunch into the radish, you’d be met with the initial bite, but beyond that first taste, the radishes were so juicy and sweet that they earned the nickname “radish sweeter than pear” and were sometimes called winter pears. Anyone who likes the small, round European radish will love the Chinese radish... |

In the Kitchen |

Chinese culinary ginger relatives

Zingiber mioga, also known as Japanese myoga ginger, is a woodland perennial that is hardy to 0 degrees Fahrenheit. It yellows in the fall, becomes dormant in the winter. This relative of common Chinese ginger is grown for its edible flower buds, which are mildly spicy and thinly sliced or shredded and used to flavor soups. The buds are also tempura fried or pickled. Alpinia galangal, also known as Thai galangal, is another rhizome related to ginger. While it is a knotty rhizome like common ginger, Asian cooks and connoisseurs would not use them interchangeably. Galangal is a fragrant rhizome popular in Indonesian, Vietnamese, and Thai cuisines. It is an important ingredient in the Thai tom yum soup... ******************************************************************************** In our family, the garlicky-oniony flavor of chopped Chinese chives (gao choy in Cantonese) harkens spring in my father’s expertly folded pork and chive steamed buns. Chives are also used to flavor stir-fries, noodle dishes, or soups. They are often added toward the end of the cooking time as they can get tough if overcooked. Blanched, yellow chives (gao choy wong in Cantonese) are milder in flavor and are a delicacy enjoyed for their tender leaves. We have a local restaurant that serves yellow chives as a condiment alongside plum sauce with their Peking duck. I also love when my mom makes a clear chicken broth that is flavored with a dash of fish sauce, sesame oil, and yellow chives. Nestled in this soup are her Hong Kong–style wontons filled with minced pork and big bites of shrimp. When harvested, yellow chives should be eaten within a day or two or they will begin to wilt. I personally like the flowering chive (gao choy fa in Cantonese) the best. It is a more substantial, garlic-flavored vegetable and is delicious stir-fried in any recipe along with other vegetables, meat, or seafood. One of my favorite dishes is a simple one made up of flowering chives cut into 2- to 4-inch lengths and then stir-fried with julienned roasted duck. Whichever type of chive you try, rinse well before using as the base of the plants can be gritty... ******************************************************************************** ...The taro “root” is the most commonly used part, but all parts of the taro plant can be eaten. Leaves are sturdy but can be eaten after being steamed or boiled for a good 45 minutes or so until tender. Then, they are eaten as any other cooked leafy green vegetable, or can be stir-fried or added to other recipes. The leaves are also sometimes used to wrap foods. As a green vegetable, taro leaves are sometimes described as similar to cabbage and contain high levels of beta-carotene. Keep in mind no part of the taro plant should be eaten raw, and all parts must be cooked first. Not only would the leaves, stems, and corms not taste good, but all parts of the plant release calcium oxalate crystals which can be toxic. Taro is extremely versatile in the culinary realm. I’ve seen it used in drinks, soups, stir-fries, and desserts. In sweet treats, I tend to associate taro with coconut as they complement each other and are often paired together. In savory foods, taro is used similarly to a potato and can be cooked in as many ways as a potato: boiled, steamed, fried, mashed, etc. I like taro sliced with a mandolin and deep-fried like chips, or filled with meat and shrimp and shaped into dumplings and fried as they are at dim sum restaurants. When I was young, I remember Chinese banquet dinners with elegant taro presentations. The taro was shredded and then formed into a bowl-sized “bird’s nest” basket and deep-fried to hold its shape. The nest would then be filled with an equally impressive stir-fry dish. Because taro tends to pick up the flavors of the other foods it is cooked with, it goes well with just about any dish and can be an unexpected substitution in recipes that call for potato, carrot, turnip, or just about any other starchy root vegetable... |

Did you Know? |

When my father does not need bottle gourds for food or products, he may grow another variety with an additional smaller bulb near the top. This double bulbed type is edible, but not desired for eating because of its awkward shape and small amount of usable flesh. However, these hourglass-shaped gourds are as symbolically auspicious as they are architecturally interesting, and they make for a beautiful decoration around the house. Called daji hulu in Mandarin, translated to “good luck gourd,” (hulu meaning bottle gourd), the name is also a synonym for a Chinese phrase that means happiness and prosperity. For decorative purposes, leave gourds to mature on the vine until the end of the season. If they are still not fully hardened, remove from the vine and store in a dry place. When fully dry, my father likes to sand these gourds to perfection. They can then be stained and even lacquered . We like to hang the gourds with a red string, a color that represents good fortune and joy. Miniature varieties sold as “miniature bottle gourds” or “baby bottle gourds” are perfect to grow and give as gifts, for adorning decorations like wreaths, or just strung here and there in the house as good luck charms.

******************************************************************************** Avoid invasive Trapa natans Beware: Trapa natans, also called water chestnut, is not the edible Chinese corm eaten as a vegetable. This water chestnut is an invasive aquatic plant that chokes out native aquatic plants along streams and lakes in the Northeast part of the United States. This annual plant appears as a rosette of small fan-shaped leaves that sit on the surface of the water. Underneath, air bladders near the top of long stems help keep the plant afloat. In late summer, the invasive plant produces seeds with four sharp spines on them that somewhat resemble Eleocharis dulcis. These seeds sink to the bottom of the body of water where they can remain dormant for over a decade until they sprout. Canadian geese may also carry the seeds to different locations. |

Our Stories |

In early winter before the ground froze solid, my father, my uncle, and my grandmother dug large pits several feet wide and deep in their nearby garden. Then, if they were lucky, they would be able to borrow a wheelbarrow or wagon for the walk further out to the family’s larger growing fields. They would harvest cold-weather crops such as Napa cabbages, radishes, and winter squash and bring them back to the pits in the garden. There, they were buried for use throughout the winter. As he told the story, I loved the image of the Napa cabbages neatly lined up and stacked several levels high. When they neared the soil line, they would be covered with dirt, leaves, and later snow and stored until they were needed. The cabbages would be buried upside down with roots facing up. This prevented the inner leaves from being covered in loose dirt. The upward-facing roots also provided an easy way to fish for and grab the hefty heads of cabbage. During the coldest days of winter, my father would go out to the pit and dig out two or three heads of cabbage which would last his family the week.

Several large and beautiful cabbages would also be buried in the pit, but stacked right side up with roots facing down. This was my family's way to designate the seed cabbages. In the spring, these cabbages would be transplanted itno the garden. When summer approached, the cabbages would flower and their seeds would be saved for fall planting. I grew up not knowing the hunger and the hard work required to stave off that hunger that my relatives just one generation back experienced. I’m saddened that this was a life my father and his family lived, but I am also empowered by their ingenuity. With handfuls of seed along with intellect, determination, and physical work, they created everything they needed to survive throughout the year, including the harsh winter months, in a place where refrigerators, grocery stores, and even basic living conveniences such as heat and plumbing were nonexistent. These stories keep me inspired to learn more about growing and preserving my own food... |